Iranians go to the polls: the 12th Iranian Presidential Election is scheduled to 19 May 2017

Unpredictable Elections

Highly competitive with fully-fledged campaigns, featuring strong factional rivalry, the Iranian presidential elections are notoriously unpredictable. However, while the presidency may fall in either traditionalist/conservative or moderate/pragmatic or reformist camps, the pillars or rather, strategic priorities of the Islamic republic remain the same. In general, what we tend to have seen under moderate and reform orientated presidencies is a focus on civil society, and rapprochement or détente in the region and with the outside world. We witnessed this priority under the incumbent president, Hassan Rouhani whose savvy negotiation team brokered the long-awaited nuclear deal with the P5 +1, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action implemented in 2015. On the other hand, conservatives and principlists/traditionalists tend focus on the domestic economy, and are more cautious in engaging with the west.

A second term for Rouhani? Or will it be Raisi’s time?

What are the chances of a second term for Rouhani? Historical trends suggest that the incumbent is the likely winner next month. No Iranian president has failed to secure a second term since shortly after the 1979 revolution. However, poised to face-off against hardline candidate Ebrahim Raisi – a largely unknown mid-ranking cleric, but also a loyal and trusted member of the revolutionary establishment, political observers have speculated that Rouhani may lose. Rouhani is also faces four other opponents: Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the hard-line mayor of Tehran; Mostafa Mirsalim, a conservative former culture minister; Vice President EshaqJahangiri, a moderate and reformist; and former vice president Mostafa Hashemitaba, also a reformist. The race will certainly be tight, but uncertainty also generates interest and helps drive voter turnout, which is essential in such a diverse and young society (over 60% of the 80 million population is under the age of 30).

Other factors that suggest Rouhani will have a comeback is the vetting agency, the Guardian Council’s choice to exclude former hardline president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from the candidate list. It demonstrates that the Supreme Leader does not want to rock the boat, that is, he is hoping for a high turnout to the polls and it reaffirms his preference for a two-term presidency. It also indicates that the Supreme Leader wants to avoid a campaign that exacerbates political division.

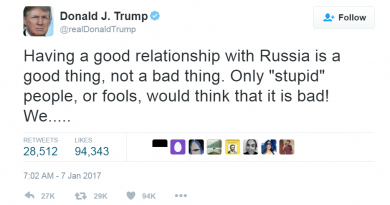

However, there are reasons why Rouhani may not win a second round. Rouhani’s presidency was directly related to the sense of crisis in Iran in 2013. The economy was reeling under the pressure of heavy sanctions, and with the unresolved nuclear dossier the risk of a US strike on Iran was ever-present. The Supreme Leader reluctantly supported Rouhani’s efforts, warning of America’s untrustworthiness. Rouhani succeeded in brokering the historic nuclear deal, however, Iran’s expectations of the economic benefits of the nuclear deal have not yet materialised. Rouhani has restored a sense of security by preventing hyperinflation and shortages, but unemployment remains high, particularly among young people. The remaining primary US sanctions, coupled with the uncertainty surrounding the Trump Administration’s policy on Iran, have made many western European firms unwilling to risk business deals with Iran. This is compounded by the refusal of financial institutions to process payments for contracts involving Iranian counterparts.

The Iran-US nuclear deal as the central problem

In fact, the aftermath of the nuclear deal is where the problem lies. What did the nuclear deal bring with it? The fiery rhetoric continues from Washington even though Iranians believe that they have exercised good will. Recently, Iranians were victims of Trump’s travel ban, as well as ongoing confrontational rhetoric. These actions have emboldened Iranian hardliners who argue that Rouhani’s conciliatory approach has been abused by the USA and that his team conceded too much. If we recall in 2000/2001, reformist president, Mohammad Khatami called for a ‘dialogue of civilisations’; in return, George W. Bush placed Iran on the ‘axis of evil’. This opened the way for harsh criticism of the reformist movement, intra-factional wrangling, paving the way for the entry of hardline president, Ahmadinejad. Could we see a similar pattern in May? What is patently clear is that the international treatment of Iran has repercussions on its political orientation and indeed on the outside world. A hardline victory would put conservatives on a collision course with a confrontational Trump administration, endangering the 2015 agreement that put limits on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. The countdown begins for not only Iran’s fate but the future international political climate.

Iranian President, Hassan Rouhani. Photo by The Kremlin / Public domain

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.