Chinese Military Reform: An Assessment

In the last few years several important military reforms have been underway in China under its leader Xi Jinping, and they are continuing nowadays. These reforms, already defined as the most important in China since 1949, can possibly conduct Chinese military power to a higher status among the most important military powers in the world, and will give a complete different shape to the Chinese armed forces. These military reforms, moreover, are interesting because they could be seen as a consequence of the actual process of power centralization promoted by Xi Jinping, involving in this sense not only the Army organization, but also the balance of power in the political-military relation in China.

People’s Liberation Army reform: an overview

Until few years ago, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was modelled on the Soviet Red Army organization of the 1950s, i.e., was focused on the disposition of huge masses of military personnel on the ground, being almost unable to develop a joint command and joint doctrine, and keeping the armament and the military technology dependent on the Soviet Army; in other terms, Chinese Military was more focused on quantity than quality and structure.

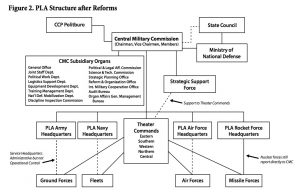

Under this model, the PLA’s organization saw the Central Military Commission (CMC) at the top of its organization, being the CMC strictly linked to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Under the CMC there were 4 departments – the General Staff, the General Political department, the General Logistics department and the General Armament department –, the Navy, Air Force and Second Artillery Headquarters – being the latter related to rocket and nuclear warfare – and 7 military regions, that with the General Staff were conducting the ground forces.

Within the framework of Xi Jinping’s reforms, the new PLA organization will aim to, inter alia, establish a national- and a theatre-level HQ for ground forces, turn the Second Artillery department into a fully-fledged service, and create a Strategic Support Force to manage the “information domain” including space, cyber and electronic warfare activities.

In a process started in 2015 and that will end only in 2020, or later, Xi Jinping’s reforms have already changed quite a lot the shape of the PLA. The CMC have been restructured in 15 departments and commission, the 7 military regions have been reorganized into 5 geographical-operational theatre commands, and each branch of the Army has been reorganized as a service HQ for the forces, so that the administrative services were separated from the operational dynamics. Finally, the reforms will aim to strongly reduce the personnel of the Chinese Army, in a process that has seen the total number falling from the 3 million personnel of 1997 to the 2,300 million of 2005; in 2015 Xi Jinping announced that this feature will be reduced of another 300,000 personnel by 2017, most of them being non-combatant personnel.

Source: Phillip C. Saunders and Joel Wuthnow, China’s Goldwater-Nichols? Assessing PLA Organizational Reforms, National Defense University, April 2016, http://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratforum/SF-294.pdf

Which future for the PLA?

Beyond the organizational consequences, the PLA reform has several consequences from the strategic point of view and, above all, from the political point of view. The new organizational structure – the real core of the reform – associated to the improvements of the Chinese armament of the last two decades and the reduction of the PLA personnel imply a drastic shift of the PLA towards a more modern model of armed forces. Saunders and Wuthnow claim that PLA’s organization changes move the Chinese army closer to the US armed forces model, in which the operational services are separated from the administrative services. Nonetheless, Chinese reformers have not just copied the US model, but they adjusted it to their national peculiarities: as Hu Jintao affirmed in 2012, the main aim of the reforms – not yet implemented at the time – was to ‘modernize the military organizational structures, and build a system of modern military forces with Chinese characteristics’. In general terms, the main aim of the reforms is to improve the military quality of the PLA while reducing its dimension; to do so, the organization of the PLA has been revised, while on the other side Chinese military R&D and weapon improvements are trying to reduce the technology generation gap between the PLA and the others military powers as much as possible.

From a political point of view, this reforms could be read as the result of the tightening political control of the CCP on the military establishment. From this point of view, ‘Core Leader’ Xi Jinping’s longa manus is clearly evident: the new organization of the CMC allows a stricter political control on the military elite, that recently has been in the centre of a corruption scandal that led to the arrest of two former PLA generals, Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong.

Finally, Michael Chase, Jeffrey Engstrom and Roger Cliff offer two possible takes of the reform of the PLA.

The first one, the optimistic take, affirms that the reforms of the PLA aim to create a leaner and more modern Chinese military that will be able to conduct more efficiently joint operations; from a strategical point of view, this reorganization aims to create a powerful enough system to improve strategic deterrence or even, if necessary to take on powerful potential adversaries including the United States – nonetheless, the military budget gap between the two powers is still huge and prevents the two military system to be even comparable.

The second take, or pessimistic take, asserts that the military reform of the PLA will improve Chinese military capability, but still these reforms are not coordinated with the core of the Chinese military doctrine – i.e., focussed on manoeuvre and undirected attack, for that a highly decentralized system is necessary instead of a strictly centralized system like the actual one: this discrepancy could prevent reforms from being efficient.

The sources for this articles are: US Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016; Cordesman, Anthony H., China Military Organization and Reform, Center for Strategic & International Studies, Washington DC, August 2016; Qingren, Shi, China’s Military Reform: Prospects and Challenges, Asia Paper, Institute for Security and Development Policy, Stockholm, September 2014; Saunders, Phillip C., and Wuthnow, Joel, China’s Goldwater-Nichols? Assessing PLA Organizational Reforms, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Washington DC, April 2016.

Soldiers of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA). Photo by Chad J. McNeeley / CC BY 2.0

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.