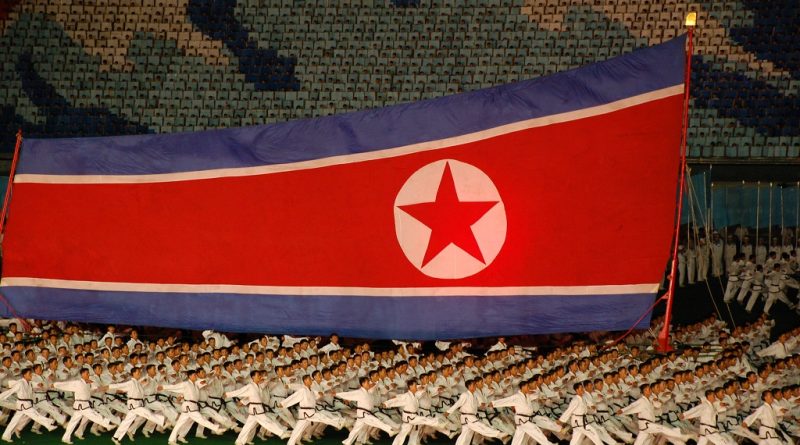

Shockwaves from North Korea

On September 3rd, North Korea conducted a sixth nuclear test, by far its largest to date. According to a state’s spokesperson, the rogue nation successfully tested a hydrogen bomb designed to be mounted on an intercontinental ballistic missile. The energy released is believed to measure between 50 and 120 kilotons, a significant leap from previous efforts, which have never been greater than 10 to 20 kilotons. While a previous H-bomb claim made back in January 2016 was met with skepticism by experts given its comparatively small yield, there is now less room for doubt. The test took place only five days after North Korea sent a ballistic missile soaring over Japan, an action which prompted an emergency session of the Security Council, only a few weeks after it imposed the hardest sanctions to date on Pyongyang. A second session was arranged for September 5th to discuss the new developments.

The aftermath

South Korea has since carried out tests to simulate an attack to North Korean nuclear facilities, and has announced that it will temporarily deploy the four remaining launchers of a U.S. Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile shield, the most advanced interceptor of ballistic missiles in the world. The situation is poised to escalate even further, with South Korean experts and commentators calling for the country to develop its own nuclear weapons (a policy approved by 60% of the population, according to a 2016 survey), and with talks of redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in the peninsula, along with a Seoul-Washington agreement for the purchase of thousands of millions of dollars in weapons and other military equipment. However, U.S.-South Korean relations have not been at an all-time best as of late. Back in June, South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in suspended the deployment of the aforementioned U.S. missile defense system, while in turn, President Trump is aiming to withdraw his country from the U.S.-South Korea free-trade agreement. In addition, the U.S. leader has previously questioned the stationing of U.S. troops in South Korea and Japan, and hinted that the two countries should look to pursue their own nuclear weapons. His public statements regarding U.S. commitment to protect U.S. allies from North Korea have also been less than reassuring, and Trump has criticized South Korea’s ‘talk of appeasement’ with their Northern adversary.

In the meantime, the Japanese Prime-Minister Shinzo Abe has claimed to have reached separate agreements with both the U.S. and Russian Presidents on cooperation over North Korea. Furthermore, in the sidelines of the BRICS summit, Putin and Xi vowed to ‘appropriately deal’ with North Korea, sticking with the goal denuclearization in the Peninsula. The two countries have also been proposing a freeze on North Korean nuclear and missile efforts in exchange for a cease of U.S.-South Korean military drills, but the suggestion has been seen as a mistake by the U.S. Administration, although the South Korean President claimed back in June to be open to the idea.

The role of China and other remarks

Trump was quick to point out that the last nuclear test was an ’embarrassment’ to China, who was “trying to help but with little success“. It would certainly appear so. The timing of the events that unfolded on September 3rd, occurring as world leaders arrived in China for the BRICS summit, has been considered by analysts a provocation against the state. While China has recurrently condemned North Korea’s nuclear tests, and has recently shown some flexibility on stronger sanctions against the rogue state, it would appear that for the time being, Beijing is more concerned with the fallout from the hypothetical political collapse of Pyongyang, which would lead millions of refugees to his borders, and U.S. troops closer to Chinese soil. Moreover, the chance of a North Korean nuclear strike against China is seen as a remote possibility, and Xi Jinping is currently facing a power struggle at the highest levels of the Communist Party, making any radical measures, such as cutting off Pyongyang’s oil supply more unlikely.

China is also butting heads with South Korea and the U.S. over military drills and missile defense. It is also unclear at this point whether the alliance will be further damaged if prove comes to light that Pyongyang can reach the continental U.S. with a nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile. Such a scenario is further worsened when considering that the hermit state has proven to be more than capable in the realm of cyber warfare, potentially disrupting attempts at nuclear crisis management.

These problems are particularly worrisome, and call out for more unity amongst the major players involved, which is something that has been lacking up to this point. Progress has occurred in the imposition of sanctions, but in that regard, Trump is right: China has not done enough. Given that North Korea conducts 90% of its trade with China, there is certainly room for further sanctions, particularly in the oil and textile sectors. Illegal financial ties between Chinese and North Korean banks must also be addressed. However, in order for such steps to be taken, it is necessary for rules to be established in case the Pyongyang regime is destabilized to the point of rupture. An agreement regarding future U.S. presence in the peninsula, and joint efforts to accommodate future refugees traveling to the Southern and Western North Korean border may persuade China to do more in this area. Not to mention, any hopes of successfully reuniting the Korean Peninsula require Chinese involvement at its core.

Diplomacy should be always on the table, and it was on that basis that Moon Jae-in was elected. The results have been negligible so far, although it’s still early days. Preemptive strikes become less and less attractive with every technological breakthrough of the North Korean regime, which is also believed to be developing second-strike capabilities. As it has been said frequently, there are no easy solutions. In the meantime, it is also important to consider the dangers brought on by North Korea’s nuclear and missile proliferation – particularly if the regime falls.

Photo by stephan / CC BY-SA 2.0

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.